Some Stories from Derek Parfit's Biography

Or: stories about a genius who crushed his most prized possession

Beyond having an exceptionally interesting and important philosophical corpus, it turns out that Derek Parfit also had an exceptionally interesting and noteworthy life. I now know the latter of these things because I am reading David Edmonds’s excellent biography of him (and his ideas), Parfit: A Philosopher and his Mission to Save Morality. I’m halfway through it, but it’s already one of my favorite reads of the year.

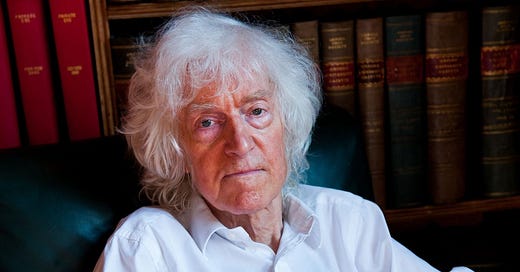

There is an unbelievable density of hilarious and insightful anecdotes in this book. I want to reproduce a number of these here. I will try to give enough context for each that by the end of this post you understand the at once comical, brilliant, and bizarre (first half of) life of Derek Parfit. As a primer, you should know that Parfit (1942-2017) was a British philosopher whose work serves as the intellectual foundation for Effective Altruism, longtermism, and a great number of hotly-debated topics in academic philosophy.

Some Stories

One theme from the early sections of the book is that Parfit was an unparalleled student. I invite you to take a moment to reflect on the things you did, thought, and produced at the age of thirteen. At that age, here’s what Parfit was writing:

A large faded yellow manuscript floated towards me. It was slightly curved, as if it had once been rolled up. On it was written in a beautiful Elizabethan hand an intricate story of curves and finery. The sun smiled pleasantly on it, and reflecting that contentedness, it drifted towards me, strange but stately, until the words were as large as a row of oranges. The orange rays of the sun shone on it, and then through it, and the words faded away.

And, later in the same piece of short fiction:

And the echo rang and whispered down the valley to the distant sea, and the breeze blew into a wind. The cypress trees shook, the fountain totterred crazily, and the ivy was ripped from the trembling pillars. The wind howled into a gale, the sky grew dark, the cypress trees were torn from the ground and rolled madly over the paving stones, the fountain hurled its sodden mist against the soft-orange tiles, spluttered, and died, and the pillars crushed into the dying lillies in the trampled grass below the first. The valley darkened and a thundercloud hung above. The last tree sank down, defeated, and all was black. And then I felt a change, everything was harsh, and uneasy … [sic]

I was staring at the blank ceiling of my room. A great rush of longing sadness came over me. I realised now the beauty of the things I had seen and scorned, and I wept bitterly because I knew they were lost for ever. (Chapter 2)

His writing was beautiful and mature. Often I wonder what my skills in many areas, including writing, would look like if I hadn’t squandered so much time on mindless entertainment in my teens. I am sure I would not have, however, approached Parfit—at thirteen!

Parfit had an exceptionally clever mind. Here’s an amusing and impressive story from his final year as a King’s Scholar at Eton (in other words, as a recipient of the most prestigious scholarship at the best secondary school in England):

Derek was known for his love of linguistic games and puzzles: he might, for example, take a poem and divide up the words or stanzas in a new way. Six decades later, a fellow pupil could still recall examples of his word play—such as a line he was doodling at his desk: “have some fundamental knowhow about American canticle melody,” which he transposed into “have some fun, dame, ‘n’ talk. Now how about a meri can-can—ticle me, lady.” (Chapter 3)

Parfit studied history in his undergraduate years at Oxford. At the start of his final (third) year, he sat an optional exam for the Gibbs Prize in history.

What his tutors and examiners never found out was that he was not above inventing quotations in his exams. His motivation was simply to get the best possible marks—he mentioned to one friend that he had invented quotations from Otto von Bismarck. He loathed Bismarck more than just about any other historical figure. (Chapter 5)

He was graded first and won the Gibbs nevertheless. This was hardly surprising. He got the top score on every examination he ever took save two.

After spending some time in the US after his history degree at Oxford, he fell in love with philosophy. It was from then on to be his lifelong obsession.

Parfit was heading back to Oxford and the BPhil. He had at least decided definitively to shift disciplines. As his friend Edward Mortimer put it, “The rest is … well, not history I suppose.” (Chapter 6)

Edmonds’s book is littered with quips like these, which I suppose are characteristic of philosophers. Here’s another from one of Parfit’s colleagues at the draconian traditionalist All Souls College, Oxford, where Parfit spent his entire mature academic career:

The All Souls political philosopher Jerry Cohen once wrote a paper defending his objections to change. It begins as follows:

“Professor Cohen, how many Fellows of All Souls does it take to change a light bulb?”

“Change?!?” (Chapter 7)

Cohen was hardly exaggerating the insistent traditionalism at All Souls. Only after heated debate was the first female Fellow admitted to All Souls. And this decision was not met with candor by all:

Upon seeing a female Fellow come down for dinner, the geneticist E.B. Ford stood up, declaimed, “There is a woman present,” and promptly fled the room. When he bumped into another of the early XX-chromosome Fellows, the geneticist swung his umbrella at her and screeched, “Out of my way, henbird!” (Chapter 10)

This recalls the tremendous racism and homophobia of the geneticist and discoverer of DNA James Watson. Beware of bigoted geneticists!

Another incredibly surprising piece of the Parfit puzzle is the sheer scale and stature of the philosophers he knew and who respected him. In many cases, as Parfit seeked out various academic appointments, he applied with glowing recommendations from each of the top five living philosophers. He left an impact on many contemporaries, as well:

The impression [Parfit] made on [Peter] Singer lasted a lifetime: “Of all the philosophers I have known since I began to study the subject more than fifty years ago, Parfit was the closest to a genius. Getting into a philosophical argument with him was like playing chess with a grandmaster: he had already thought of every response I could make to his arguments, considered several possible replies, and knew the objections to each reply as well as the best counters to those objections. (Chapter 7)

Parfit’s impact, even immediately after the publication of his first book Reasons and Persons in 1984, was not limited to academic philosophy circles. Aside from being one of the best selling works of contemporary philosophy of all time, it reached an unlikely corner of the world:

Parfit was aware of the similarities between his writings and Buddhism and discussed them in a short appendix to Reasons and Persons, pointing out that the Buddhist term for an individual is santana, or “stream.” Later, he was delighted to discover that Buddhist monks had been heard chanting passages from the book. (Chapter 8)

His witty philosopher friends loved to poke fun at his eccentric lifestyle, something like a monk asceticism for philosophy:

Derek really does seem to live wholly in his mind. He treats his body like a mildly inconvenient golf cart he has to drive around in order to get his mind from Oxford to Boston to New York to New Brunswick. [...] And he sees others as pure minds similar to his. (Chapter 8)

Larry Temkin, an early mentee (to the greatest extent that Parfit could mentor a student, which is to say not very much) of Parfit’s and later among his closest friends, gave one of the most incisive comments on his development of character:

I believe that when Derek was younger, he regarded his relationship with academic subjects as a kind of game. A very enjoyable one that he was really good at. He enjoyed the combative side, of “beating a foe” on the field of intellectual debate. When he was doing history [...] it made sense for Derek to “play the game” he was so good at, while retaining the characteristics of a normal, very smart, young person enjoying themselves and the company of others, as well as a host of stimulating pursuits. But, when he realized that he could be massively successful at philosophy, and then, more particularly, that he could make important and lasting contributions to moral philosophy, he was now dealing with isues that really mattered. (Chapter 8)

This was, perhaps, when he changed into a singularly-focused man, doing nothing but philosophy. He was not only singular in choosing philosophy, but singular in choosing within philosophy. In other words, he was only really interested in research broaching moral philosophy. And within moral philosophy, his list of admired work was short. There’s a great story from his time “mentoring” Larry Temkin while Temkin was a graduate student at Princeton and Parfit was visiting faculty:

Parfit and Temkin would become close, but in 1977 the teacher inadvertently nearly stymied the career of the student. Temkin was preparing for his oral exam, a “comprehensive” exam, which would partially be about utilitarianism and which he was required to pass to move to the dissertation stage. “What should I read?” he wanted to know. “Sidgwick’s The Methods of Ethics,” Parfit replied. Temkin had to travel to New York to get hold of a copy, and when he’d read this huge tome, he went back to Parfit. “What should I read next?” He replied, “Reread Sigdwick.” Temkin reread it and approached Parfit again; “Is there anything I should read on utilitarianism besides Sidgwick?” Parfit advised him to reread Sidgwick a third time, rather than devote energy to inferior writings. Eventually it came to the oral exam. Temkin was questioned about various standard books and papers in the field, but not having read them was unable to comment. One examiner was exasperated: “Larry, this is supposed to be a comprehensive exam—what have you read?!!!” At which point another of the examiners, Derek Parfit, “raised his finger and emphatically interjected, ‘He has read Sidgwick!!!’” (Chapter 9)

This is one of my favorite stories from this half of the book. What a strange and fortunate thing it would have been to have Parfit as your mentor! And how could Temkin have possibly gone along with this advice from Parfit?

That Parfit was preeminent among Oxford philosophers in this period is made ever more impressive by the brilliance (and sometimes impossible arrogance, which Parfit did not possess) of his contemporaries. One story, about Bernard Williams, a moral philosopher with whom Parfit shared many seminars and few opinions, comes to mind:

After listening to an academic lecture [Williams] might say, “I have five objections to your thesis,” and would then reel them off one by one. Observers suspected that he had plucked the number “five” at random and was making it up as he went along. It was a way of challenging himself while peacocking his brilliance to others. (Chapter 10)

One of the things I enjoy most about Parfit’s writing is his use of clever, thought-provoking, and oftentimes hilariously absurd thought experiments. Though never with quite the same sharpness or consistency as Parfit, other philosophers have used this strategy as well. Here is one that Williams promotes as challenging for consequentialists to address:

[Williams’s] case [against consequentialism] is built on two hypothetical scenarios. First there is George, an unemployed chemist who is offered a job developing biological and chemical weapons. George is adamantly opposed to such weapons, but knows if he doesn’t take the position, somebody else will, and will pursue the work with far more zeal. Plus, George needs the money.

Then there is Jim. Jim is on a botanical expedition in South America when he comes upon a terrible scene. Twenty indigenous villagers have been tied up, and a heavy man in a sweat-stained khaki shirt, who turns out to be the captain in charge, explains that all twenty are about to be executed for protesting against the government. However, since Jim is an honoured visitor from another land, the captain offers him the choice of killing one of the locals himself, after which the others will be set free. If Jim doesn’t take up the offer, the captain’s men will execute all twenty. (Chapter 10)

He’s no Parfit, but sometimes I do wonder about Jim. (George should take the job.)

In his late 30s, Parfit applied to become a more permanent Fellow at All Souls. This was the natural progression for one of his talent, and he was only potentially held back by his eccentric interactions with College members and his lack of a concrete record of publications. The more senior members of the College, including future Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen, knew better—Parfit was a once-in-a-generation genius. Academic spats are greatly entertaining:

At the Parfit vote, Sen was outraged that “some silly idiots thought that it should all depend on how many books you’d written.” “The great men defended him,” [Fellow William] Waldegrave remembered, whilst “the less distinguished middle-aged scholars who were very proud of their own mediocre publishing lists were the ones who criticised him.” (Chapter 10)

Parfit had a number of strange habits, including some that transcend even workaholism—and logic:

Toothbrushing took up more of his time than eating. He would buy toothbrushes in bulk with a brush attrition rate of roughly three per week. And during one tooth-brushing session he could read fifty pages. (Chapter 11)

It’s no wonder he worked himself nearly to insanity, particularly in the stretch leading up to the publication of Reasons and Persons:

He had finished a draft of the conclusion, but his brain could no longer process the text. “The words are swimming on the page,” he said. “I’ve got to sleep.” (Chapter 11)

Perhaps Parfit’s most infamous habit was photography. There is much to say about this obsession of his: that he travelled across the world at least twice every year to photograph buildings; that he only ever photographed the same five or so buildings, exclusively in Venice, Oxford, and St. Petersburg (what!?):

He would take shots of the same building countless times. “I may be somewhat unusual in the fact that I never get tired or sated with what I love most, so that I don’t need or want variety.” (Chapter 13)

There’s also that he waited so patiently for the right lighting that he was more than once found waiting in the snow, seemingly not noticing that his fingers and nose were nearing an irrecoverable accumulation of frostbite. The most absurd bit, however, is the length to which he went to perfect his images, and what he did with them subsequently. Here’s the story of one of his most expensive pictures (on which he spent several thousand 1980s pounds):

after seven iterations [of sending the photograph to and from a professional film developer …] the photograph emerged that was now on the wall in his study. “Here, if you like it, take it,” said Parfit, offering it to his former student. Given the expenditure and effort that he had put into the photograph, this was an outlandishly generous offer, and one [Larry] Temkin felt obliged to refuse.

A year later, Parfit arrived at Rice University in Houston to teach a course, which Temkin had fixed up. He carried with him one small canvas bag, in which he stuffed everything he thought he needed for his three-week visit, and before even unpacking he told Temkin that he wanted to hand him a gift. He rummaged around in the bag, pulling out shirts and underpants and books, until he found what he was looking for—the photograph Temkin had so admired. It was completely ruined. He’d crumpled it up. (Chapter 13)

Parfit handed it to him, probably with a smile. This, I think, is the most immaculate story about Parfit. It defies all understanding. “Who does this? Only Derek could do this,” Temkin later remarked.

His obsession in photography was nearly matched by his obsession with perfection in his bookwriting. He demanded specific fonts, page layouts, covers, colors, and much more for his publications. Not to mention that he made changes to the text straight on up to the publication date. In the run-up to printing of the paperback version of his first book,

Once again, he drove his copyeditor and other [Oxford University Press] staff involved in the book to the edge of sanity. “He was solipsistic. The book’s called Reasons and Persons but he had no idea about other persons.” (Chapter 15)

In academic debate, however, Parfit was a model of brilliance and humility. Among a discussion group of eminent philosophers, “It was obvious [...] that Parfit was the one who cared most about the truth and the least about victory” (Chapter 15).

Parfit’s life, fortunately for posterity, did not come to an end upon the publication of Reasons and Persons’s paperback edition. When I finish Edmonds’s book, I’ll do a part two to this post. Until then!